My shopping cart

Your cart is currently empty.

Continue ShoppingWhen you shop online this holiday season, you'll run across countless products - from shoes to blankets to shirts - featuring designs inspired by indigenous cultures. So, if there's such a huge demand for Native art, why do Native communities remain some of the poorest in North America? And why do large brands that see business opportunity in products featuring Native aesthetics and themes so rarely collaborate with Native artists?

Well, for one, both the producers and consumers of these products have been exposed to a lifetime of media depicting Native peoples in really limiting contexts. Here's a few of the most common:

Almost all mainstream media over the last 400 years has shown us in one of these ways. As just one example, the iconic "End of the Trail" image, which was based on a sculpture by James Earle Fraser, encompasses all three of these contexts. He described this work as depicting the American Indian's "exit into oblivion."

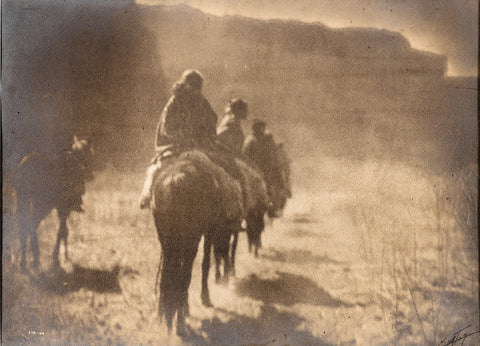

The enduring popularity of Edward Curtis, a photographer who often staged his sepia toned images, has also perpetuates these rudimentary ideas about Native people. His work was recently featured at the Seattle Art Museum, just a block from Eighth Generation's retail store. The following picture is from his 1909 book titled "The Vanishing Race."

In the 1970s, a crying Indian portrayed by a bronzed Italian American actor made for an effective PSA against littering. The Native person, who is literally the personification of the plants and trees, can manage a tear but no dialogue.

Eighth Generation has crashed into these entrenched stereotypes countless times - from popular mainstream media media's undying instance that we are a non-profit - because how could a Native company reach this scale? - to customers who expect our products to be hand made - because it seems that Native-owned implies hand made? The reality for Native-owned companies is that the public often measures our work against these outdated stereotypes while rarely applying the same standards to other business producing the same products. You either get on board with the selling power of popular pan-Indian tropes like teepees and "spirit animals" or you end up spending a large portion of each day explaining why trying hard, using technology and being a global citizen is ok.

Our story illuminates the extent how public perceptions of Native people fall very short of accommodating highly skilled, hard working professionals who would make great business partners or collaborators. This is why online retailers are flush with Native-inspired products instead of meaningful collaborations with Native artists hungry for opportunity.

At Eighth Generation, we understand that appropriation is about more than hurt feelings. It has real cultural and economic consequences. So in addition to creating Native-owned and designed products, and modeling responsible ways of partnering with Native artists through the Inspired Natives Project, we are committed to raising awareness around the importance of supporting Native artists and businesses. We try to embrace the opportunity to address outdated stereotypes and tropes.

We think we're on the right track, but there's a long way to go, and YOU can help! Before you buy Native art or a product featuring Native art, just ask three simple questions:

1. Is the artist Native?

Generally, this means the artist is enrolled or registered in a tribe. If you don’t see the artist’s name or tribe on the packaging or website, the product was NOT designed by a Native artist. And don’t be fooled by the term “Native-inspired”, a term that grew in popularity after the passage of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, which made it illegal to call something "Native" when Native people had nothing to do with it. So saying a product is “Native-inspired” is often an attempt to mislead consumers into thinking the product is connected to real Native peoples without violating the law.

2. Is the company Native-owned?

There aren't yet a lot of Native-owned companies that you can buy products from, because there just isn't a lot of start up capital or business capacity in our communities. So it's especially important to support Native peoples that still managed to pursue success through entrepreneurship. The more you support Native-owned businesses, the more business knowledge cycles back into our communities and fosters sustainable, self-determined models for Native artists creating arts-based businesses. If you’re not sure, don’t be afraid to ask!

There aren't yet a lot of Native-owned companies that you can buy products from, because there just isn't a lot of start up capital or business capacity in our communities. So it's especially important to support Native peoples that still managed to pursue success through entrepreneurship. The more you support Native-owned businesses, the more business knowledge cycles back into our communities and fosters sustainable, self-determined models for Native artists creating arts-based businesses. If you’re not sure, don’t be afraid to ask!

3. Is the artist being fairly and equitably compensated?

When a Native artist licenses artwork to a company, they’re signing off on more than just their artwork. They are also granting permission for the company to tell their personal story and align with their tribe. With these greater stakes in mind, it's especially important to be aware of that fact that not all licensing arrangements are equal.

Although agreements will vary widely based upon the stature of the artist and the size of the company, they generally include a combination of an upfront fee, and royalties based on sales and product exchanges. However, you will hear of arrangements that vary as widely as companies deliberately seeking out artists who do not have a voice, and purchasing the rights to artwork in perpetuity for $200 -- to arrangements like Eighth Generation's Inspired Natives Project, where artists receive an upfront fee, royalties, access to product, and invaluable capacity building. There's no one right model, but remember that it's OK to ask. They may tell you it’s confidential, but the way they handle an inquiry says a lot about their values.

Although agreements will vary widely based upon the stature of the artist and the size of the company, they generally include a combination of an upfront fee, and royalties based on sales and product exchanges. However, you will hear of arrangements that vary as widely as companies deliberately seeking out artists who do not have a voice, and purchasing the rights to artwork in perpetuity for $200 -- to arrangements like Eighth Generation's Inspired Natives Project, where artists receive an upfront fee, royalties, access to product, and invaluable capacity building. There's no one right model, but remember that it's OK to ask. They may tell you it’s confidential, but the way they handle an inquiry says a lot about their values.

With the information you acquire from asking these 3 questions, you'll be able to make an informed decision about whether to buy. Regardless of which way you decide to go, we remind you that resources used to buy appropriated artwork leads to more appropriation. More appropriation leads to a further decrease in the already limited opportunity for cultural artists and Native-owned businesses.